The Sentencing Council is examining whether pregnancy should be a stronger reason not to send a female offender to jail.

It launched a consultation last month which will examine the potential impact of being pregnant and giving birth as a prisoner, and it’s due to publish its decision in November.

Current guidance only suggests that judges “may consider” pregnancy when sentencing.

Campaigners say there is no statutory duty to consider it, and judges often don’t – and that unborn babies are put at risk in prison and shouldn’t be punished for their mother’s crimes.

Others argue pregnancy shouldn’t be used as an excuse to dodge punishment.

Sky News has spoken to three women who’ve experienced pregnancy in jail and described a frightening, isolating and humiliating experience.

One we will call ‘Olivia’ said being sent to jail pregnant was “traumatic beyond words… terrifying, lonely and deeply unsettling”.

She said: “There aren’t the midwives, there’s not the 24/7 support. If someone has a medical emergency, how many sets of keys does it take to unlock all the doors to get through?

“And that’s before you can even get into the prison to get the paramedics or the midwife to the woman.”

‘Laying in a bed of blood’

Another woman, ‘Susie’, said she had no one to turn to when she thought she had miscarried her baby in her cell.

She said: “They didn’t realise that I was still laying in a bed of blood.”

She added she had “a horrifying wait” all weekend to get her situation checked with a scan.

MORE ON PRISONS

- Low-level offenders to be released early under plans to free up prison space

- More foreign prisoners to be deported to free-up cells and tackle overcrowding

- Rapists to serve full sentences and low-level criminals to avoid prison through ‘Texan-style’ justice reforms, Alex Chalk says

Susie says prison life is unsuitable for a pregnant woman: “I got a lot hungrier, and they told me that they wouldn’t provide me with more food, and I didn’t have a pregnancy mattress.

“I feel like as you gain more weight, your body’s pressing into the bed and you spend an awful lot of time in your room.”

A handcuffed birth

A third woman, ‘Anna’, who also wants to remain anonymous, describes her experience as “humiliating” and says she gave birth while handcuffed to a prison officer.

She says the officer “told me to be grateful that she was putting me on long cuffs and not short cuffs”. These are cuffs with a longer chain.

Anna says that only when she had a second pregnancy outside of prison, did she realise how substandard the care is for women behind bars.

She said while in prison: “I had appointments that had been missed. I had a scan that was coming up. I ended up missing that a couple of times because they never had the staff to take me.

“Eventually I went and was taken through the front of the hospital in handcuffs. That’s very degrading and humiliating.”

She added: “When I went into labour it was early hours in the morning at 5.30am. I pressed my cell bell. An officer told me that somebody would be with me soon. But nobody came.

“I pressed it another three, four times. Nobody came. They only then unlocked me at the same time they unlocked the rest of the landing.”

Anna added: “I didn’t see the nurse till about 9.30 in the morning. I wasn’t sitting in an ambulance to go to the hospital until around 10.30am. I had been told that the ambulance was there, but it was waiting outside of the gates because it had to be security cleared to come into the prison.”

Ministry of Justice figures show that three births took place in prison or in transit to hospital in 2021-22.

The case of Aisha Cleary

In July this year, an inquest found “serious operational and systemic failings” contributed to the chances of survival of baby Aisha Cleary, born to an inmate in HMP Bronzefield in Surrey.

Her 18-year-old mother, Rianna Cleary, gave birth alone in her cell on the night of 26 September 2019.

She called for help, but nobody came.

Aisha was found dead in the cell the following morning.

An ombudsman report into Aisha’s death published in September 2022, not only criticised the care of Rianna, but made a wider conclusion that “all pregnancies in prison should be treated as high risk by virtue of the fact that the woman is locked behind a door for a significant amount of time”.

Campaigners say it therefore follows that any prison sentence for a pregnant woman is also a sentence for a high-risk pregnancy – and a threat to their baby.

But the women we spoke to say their pregnancy wasn’t taken into consideration during their sentencing.

Read more:

Projected surge in female prison population is ‘incredibly worrying’

More foreign prisoners to be deported to free-up cells

Prison ‘never a safe place’ to be pregnant

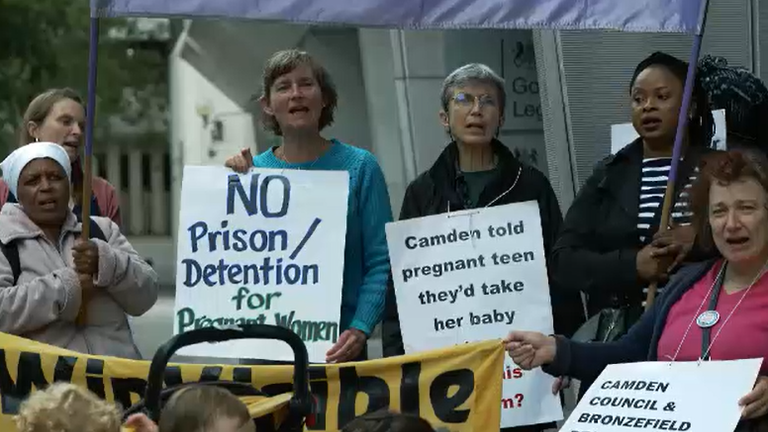

Speaking at a vigil which was held outside the Ministry of Justice to remember the anniversary of the birth and death of Aisha, Janey Starling, from the campaign group Level Up, said: “It is so evident that prison will never be a safe place to be pregnant.

“Pregnant women in prison are seven times more likely to suffer a stillbirth, twice as likely to give birth to a premature child that needs special intensive care and ultimately the long-lasting trauma on a mother and a child is devastating.”

These arguments are supported by the Royal College of Midwives and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and will inform the Sentencing Council’s decision on whether pregnancy should be a greater mitigating factor in deciding whether someone goes to jail – set against the need to punish people who commit crimes.

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “Custody is always the last resort for women and independent judges already consider mitigating factors, like pregnancy, when making sentencing decisions.

“We have made significant improvements to the support available for pregnant women in custody in recent years. This includes employing specialist mother and baby liaison officers in every women’s prison, conducting additional welfare checks and stepping up screening and social services support so that pregnant prisoners get the care they need.”

The consultation is currently open for submissions, and they are due to publish their findings on 30 November this year.

Any new guidance for judges would come into practice next April.

Source: ![]() news.sky.com

news.sky.com

Be the first to comment