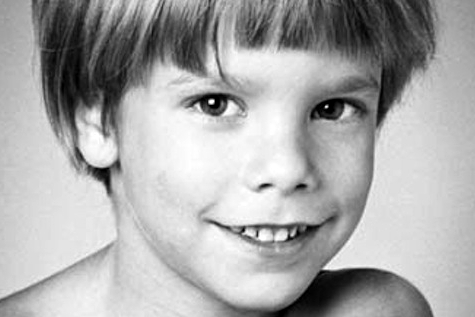

NEW YORK — Almost four decades after first-grader Etan Patz set out for school and ended up at the heart of one of America’s most influential missing-child cases, a former store clerk convicted of killing him was sentenced to at least 25 years in prison.

In a few angry words, Etan’s father condemned the convicted man. “Pedro Hernandez, after all these years, we finally know what dark secret you had locked in your heart,” Stan Patz said. “I will never forgive you. The god you pray to will never forgive you. You are the monster in your nightmares.”

His wife, Julie Patz, wiped tears from her eyes as she witnessed the culmination of a long quest to hold someone accountable for their son’s disappearance. The case affected police practices, parenting and the nation’s consciousness of missing children.

Hernandez, 56, didn’t look at the Patzes, speak or react as he got the maximum allowable sentence: 25 years to life in prison, meaning he won’t be eligible for parole until he has served the quarter-century.

The lead defence lawyer, Harvey Fishbein, told the court Hernandez wanted to express deep sympathy to the Patzes but also to say “he’s an innocent man and he had nothing to do with the disappearance of Etan Patz.”

Hernandez was a teenager working at a convenience shop in Etan’s Manhattan neighbourhood when the boy vanished in 1979, on the first day he was allowed to walk alone to his school bus stop.

Hernandez, who’s from Maple Shade, New Jersey, confessed to choking Etan. But his lawyers have said he’s mentally ill and his confession was false, and they vowed to appeal his conviction.

In a sign of the case’s impact on the law enforcement officials and everyday people enmeshed in it, the courtroom audience Tuesday included Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr., police officers who worked the case and a half-dozen ex-jurors.

Etan was among the first missing children pictured on milk cartons. His case contributed to an era of fear among American families, making anxious parents more protective of kids who many once allowed to roam and play unsupervised in their neighbourhoods.

“Through this painful and utterly horrific real-life story, we came to realize how easily our children could disappear,” said Vance, a Democrat who made a 2009 campaign promise to revisit the case if elected.

The Patzes’ advocacy helped to establish a national missing-children hotline and to make it easier for law enforcement agencies to share information about such cases. The May 25 anniversary of Etan’s disappearance became National Missing Children’s Day.

Still, Stan Patz said, he and his wife had doubted they would ever find out what happened to their child because there were “so many false leads, so many blind alleys. So many years went by.”

“Now,” he said after the sentencing, “I know what the face of evil looks like.”

From the start, Etan’s case spurred a huge manhunt and an enduring, far-flung investigation. But no trace of Etan was ever found. A civil court declared him dead in 2001.

Hernandez didn’t become a suspect until police got a 2012 tip that he’d made remarks years earlier about having killed a child in New York.

Hernandez then confessed to police, saying he’d lured Etan into the store’s basement by promising a soda and choked him because “something just took over me.” He said he put Etan, still alive, in a box and left it with curbside trash.

“I’m being honest. I feel bad what I did,” Hernandez said in a recorded statement.

His lawyers say he confessed falsely because of a mental illness that makes him confuse reality with imagination. He also has a very low IQ.

The defence pointed to another suspect, a convicted child molester whom some investigators and prosecutors — and even Etan’s parents — pursued for years. That man made incriminating statements years ago about Etan but denied killing him and has since insisted he wasn’t involved in the boy’s disappearance. He was never charged.

Hernandez’s February conviction came in a retrial. His first trial ended in a jury deadlock in 2015.

Manhattan state Supreme Court Justice Maxwell Wiley said Tuesday he’d found prosecutors’ case against Hernandez compelling. Hernandez, he said, “kept a terrible secret for 33 years.”

By: COLLEEN LONG AND JENNIFER PELTZ

Source: globeandmail.com

Be the first to comment