This is a day like few others at Westminster.

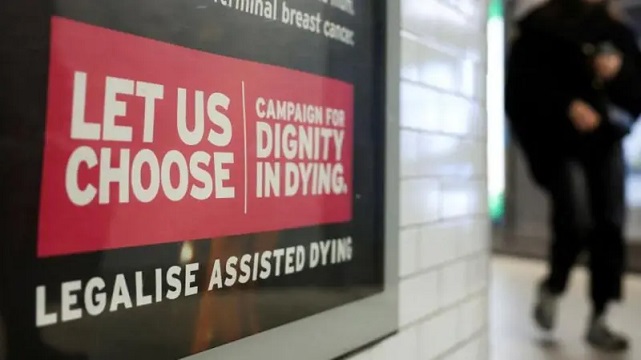

MPs have a free vote on an issue of profound social change, an issue of conscience where many have wrestled with questions ranging from morality to practicality.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill which would apply to England and Wales, will have what is known as its second reading, which is parliamentary speak for its first Commons debate and vote.

The purpose of the bill is to allow adults aged 18 and over, who have mental capacity, are terminally ill and are in the final six months of their life, to request assistance from a doctor to die.

This is subject to “safeguards and protections” which include:

• They must have a “clear, settled and informed wish to end their own life” and have reached this decision voluntarily, without coercion or pressure;

• They must have lived in England or Wales for 12 months and be registered with a GP;

• Two independent doctors must be satisfied the person meets the criteria and there must be at least seven days between the doctors making the assessments;

• If both doctors state the person is eligible, then they must apply to the High Court for approval of their request;

• If the High Court decides that the applicant meets the bill’s requirements, then there is a 14-day reflection period (or 48 hours if death is imminent);

• After this, the person must make a second declaration, which would have to be signed and witnessed by one doctor and another person.

What happens if the eligibility criteria is met?

If a person meets all this eligibility criteria, a life-ending “approved substance” would be prescribed.

This would be self-administered, so the individual wishing to die must take it themselves.

This is sometimes called physician-assisted dying and is different from voluntary euthanasia, when a health professional would administer the drugs.

As well as all the conditions set out above, the bill would make it illegal to pressure or coerce someone to make a declaration that they wish to end their life, or take the medicine.

These offences will be punishable by a maximum 14-year prison sentence.

How is this different from the current law?

Suicide and attempted suicide are not in themselves criminal offences. However, under section 2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961, it is an offence in England and Wales for a person to encourage or assist the suicide (or attempted suicide) of another.

Ms Leadbeater says the current framework is “not fit for purpose”, as people who are terminally ill and in pain only have three options – “suicide, suffering or Switzerland”.

Assisted dying has been legal in Switzerland since 1942, with the Dignitas group becoming well-known as it allows non-Swiss people to use its clinics.

Other countries where a form of assisted dying is legal include the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Luxembourg, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and some US states.

For new MPs – 335 out of the 650 members of Parliament were elected for the first time in July – it is a particularly big moment.

Shorn of their usual political compass bearings: party loyalty, ideology, an instinct on the extent or limits of the state, for instance, they have instead had to come to a very personal decision.

Parliament last considered the issue in 2015, when MPs voted down assisted dying by 330 votes to 118.

Things will get going at 09.30 GMT and the first MP to speak will be Labour’s Kim Leadbeater, who is leading the campaign for a change in the law.

She will say: “I hope this Parliament will… be remembered for this major social reform that gives people autonomy over the end of their lives and puts right an injustice that has been left on the statute books for far too long.

“A change that, when we most need it, could bring comfort to any one of us or to somebody we love.”

More on the assisted dying vote:

Others will make an equally passionate case that now is not the time and this is not the bill to make such a profound change in the law, fearing the idea is being rushed and it could lead some to feel they are being coerced into ending their lives.

Around 170 MPs have asked to speak in the debate, which will last until 14:30 GMT.

The limited time will probably mean around 50 MPs actually get to speak.

While this kind of debate doesn’t usually impose a time limit on MPs’ contributions, it will not be surprising to hear the Speaker encourage MPs to remember that plenty of others want to speak too.

So how are the numbers looking?

It is very, very hard to tell, because this is a free vote.

Neither side are sounding uber confident of victory, but I detect a bit more confidence on the side of those wanting to change the law than those who want to reject this proposed change in the law.

But both sides acknowledge there are loads of MPs who have not yet declared either way and both sides say some may only make up their mind as they listen to the debate.

“There is such a body of unknowns,” one MP – who is trying to keep a close eye on things – told me.

Those hoping to see the law change take heart from how they think opinion has shifted since the Commons last voted on the issue in 2015 and rejected change by 330 votes to 118.

Several medical bodies have gone from outright opposition then to a neutral stance now.

The turnover in the House of Commons has been huge since then too, which some believe might leave it with a more liberal instinct now.

But opponents of the bill think support and opposition might be pretty evenly matched and that any gap between the two sides is smaller than the number of MPs who have not said whose side they are on.

They also point to four former prime ministers on their side (Brown, May, Johnson and Truss; Lord Cameron has come out for the change) and they think the more time those with doubts listen to the unconvinced, the more sceptical many become.

It will be a day of harrowing stories, intellectual argument and passionate exchanges.

If the bill is rejected, that will be the end of this debate, at least in Parliament, for some time.

But it is worth remembering if MPs vote for it, it will be the beginning of the arguments rather than the end of them.

It will become one of the biggest talking points at Westminster of 2025, with further debates and votes to come.

If passed in the Friday debate and vote, the bill will have to pass many more parliamentary hurdles before it becomes law.

MPs will get a chance to debate the bill again in greater depth during its committee stage and peers will also have ample opportunity to express their views on the legislation in the House of Lords.

Source: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment