UPDATE:

Restrictions on US broadband providers’ ability to prioritise one service’s data over another are to be reduced after a vote by a regulator.

The Federal Communications Commission voted three to two to change the way “net neutrality” is governed.

Internet service providers (ISPs) will now be allowed to speed up or slow down different companies’ data, and charge consumers according to the services they access.

But they must disclose such practices.

Today, December 14th 2017, a vote will almost certainly remove a protection that some believe preserves the very fabric of the internet. Why is this happening, and what does it mean for you?

Like all great American laws, this one was written almost a century ago by a bunch of men who had absolutely no idea what they were doing.

That’s not a criticism. Who could have foreseen, as they put pen to paper in 1934, that one day their words would be used to govern how bits and bytes are streamed and downloaded, through copper, glass and radio-waves, under and overground, across our oceans and even into space?

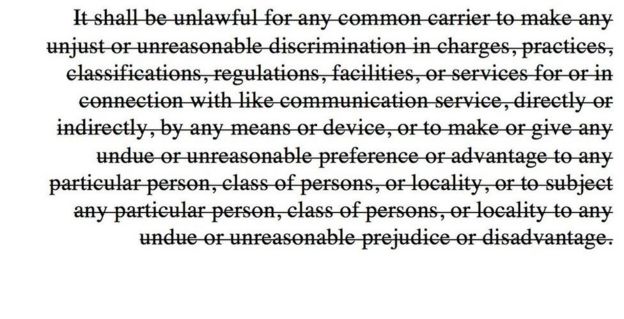

Sometimes, though, the most effective laws are about establishing a broad principle, and within the Communications Act of 1934 is one such principle that demands companies providing telecommunications do so without discrimination.

Should that rule – known as Title II – apply to the companies that provide Americans with the internet?

It did, but now it won’t.

The pioneers of the internet are unequivocal: losing net neutrality will be nothing short of a catastrophe, for innovation, free speech and free expression.

Yet the man orchestrating the change calls that notion “hysteria”.

We’re about to find out who’s right.

The decision will be made by the five-person board at the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). It will almost certainly, barring a last-minute unexpected twist, vote to overturn a decision in 2015 that said Title 2 should apply to internet service providers.

Since President Trump took office, the balance of power at the FCC has shifted to the Republicans. And this vote was brought to the front of the agenda by Ajit Pai, the president’s pick to be the FCC’s chairman.

Mr Pai has been on the FCC board for more than five years. He’s had a career mostly in government, aside from a period beginning in February 2001, when he worked at Verizon as a lawyer.

“Ah ha!” say campaigners, who believe Mr Pai’s past is an obvious conflict of interest and the motivation behind this move. Verizon, one of the biggest telecoms companies in the world, stands to benefit greatly from a loss of net neutrality.

But conversely, who better to know how the companies will react than a man who knows the business intimately?

The perceived line between expertise and vested interest is extremely thin.

In a brazen after-dinner speech last week, Mr Pai responded to the negative claims by mocking them. He showed a video comedy skit in which he attends a fictional meeting with a Verizon lawyer.

“We want to brainwash and groom a Verizon puppet to install as FCC chairman,” the lawyer says to Mr Pai.

“Awesome,” he replies.

Net neutrality campaigners say losing net neutrality will mean internet service providers will be free to trample all over the open web, slowing down services they don’t like, and speeding up ones they do.

Campaigners fear we now face an internet where you pay more to use things like Netflix, or that companies may be strong-armed into paying ISPs in order to maintain good access to their product, making things difficult for new companies who can’t afford to pay for preferential treatment.

On a broader level, those who support net neutrality argue that free speech could be adversely impacted, with ISPs able to hinder access to things the firms’ owners do not agree with, or are under pressure to quash. The internet, for all its faults, has thrived as a level playing field.

But supporters of removing net neutrality – the ISPs, mostly – argue the regulation stifles their ability to invest and innovate. They say concerns about unfair throttling and control are overblown.

Besides, this is a free market – consumers can dictate what corporations do by voting with their wallets.

The notion that there is meaningful competition for internet access in America is laughable.

The big players, Verizon, AT&T and Comcast, connect almost every American to the internet, but do so without significant overlap. In its most recent data (June 2016), the FCC determined that more than 50m homes in the US had only one choice of internet provider if they wanted fast broadband, considered to be 25Mbps or above.

“The marketplace isn’t sufficiently combative to make those kind of arguments,” said Doug Sicker, head of engineering at Carnegie Mellon, and the FCC’s former chief technology officer.

It’s unreasonable, then, to think that typical forces will mean ISPs are compelled to make choices that please their customers in case they up and leave for another ISP.

It paves the way for campaigners’ nightmare scenario, best illustrated by a tweet from Democrat Congressman Ro Khanna.

He shared, as others have in the past, a “menu” from Portuguese provider MEO. It showed how certain services, such as “social” and “music” were offered as paid add-ons.

Will ISPs in the US do the same? They insist not.

“Will Comcast block or throttle access to internet sites? No.” reads a pledge from the company.

It adds that it will not engage in any paid prioritisation – that is, deals with companies to make their services faster at the expense of others.

Verizon too has promised to uphold principles of the “open internet”, arguing net neutrality isn’t changing at all.

But FCC’s wording is perfectly clear. If internet providers want to throttle traffic, there is nothing stopping them – as long as they are transparent.

“Those obligations include publicly providing information concerning an ISP’s practices with respect to blocking, throttling, paid prioritization, and congestion management,” the FCC explained.

“Should an ISP fail to make the required disclosures – either in whole or in part – the FCC will take enforcement action.”

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, $101m has been spent by the telecoms industry in wooing the 535 members of Congress for a variety of reasons, not just net neutrality.

There is no obvious partisan divide when it comes to campaign contributions – of the top four highest “earners”, two are Republicans, and two are Democrats. The man who has received the most money from the industry is Republican John McCain, though there’s a simple explanation for that: he’s been there the longest.

Though when it comes to arguing on net neutrality, Democrats have typically been in favour of net neutrality, while Republicans, with a few exceptions, haven’t.

Republicans like to be considered the pro-business party, and the pro-business argument for ditching net neutrality is one of investment and innovation.

The ISPs, and trade organisations that represent telecoms interests, argue that until 2015, when the Democrat-controlled FCC went down strict on net neutrality, the internet was doing just fine.

“For decades, the internet flourished under a bipartisan regulatory approach that allowed it to operate, grow and succeed free of unnecessary government controls,” Verizon says.

Investment could mean faster roll out of super-high speed fibre internet. Or, more pressingly, it could improve connections for people in rural America who barely have any kind of internet at all.

But this would require that the ISPs choose to spend money in this way. The FCC’s move doesn’t involve any requirement to commit to investment in internet, rural or otherwise.

Another argument put forth by Mr Pai is that new internet providers could emerge, widening the choice for Americans getting online. He said he spoke to five small ISPs that all welcomed his plans.

“One constant theme I heard was how Title II had slowed investment and injected regulatory uncertainty into their business plans,” Mr Pai said in a statement.

“In short, heavy-handed regulation is making it harder for smaller providers to close the digital divide in rural America.”

Yet that view contradicts the one expressed by no less than 30 small ISPs this past summer. In a letter to Mr Pai, they collectively said they had “long supported network neutrality as a core principle for the deployment of networks for the American public to access the Internet”.

Mr Sicker, formerly of the FCC, told the BBC he did not see small, local ISPs sweeping the nation to offer Americans better choice.

“It would only likely happen in the same places where there is the most competition already,” he said.

“That doesn’t solve the problem for rural America and other areas that don’t have the same density. There might be some segments of America where people stand up, but I don’t think this will be nationwide.”

Also unclear is how this might impact the global picture, given the US’s important role in dictating trends and governance of a platform it ultimately invented.

European Union rules to protect net neutrality, put in place in 2016, were heralded as a “triumph” by digital rights campaigners. The changes in the US will not directly affect users outside of the country, but will further underline the philosophical differences between the American and European approach to digital rights.

The process leading up to this change has been grubby. New York’s district attorney alleges that there were two million “fake” submissions, some using identities of dead New Yorkers, made to the FCC consultation. It accused the FCC of refusing to investigate – and demanded the vote be postponed until the “massive fraud” had been looked into.

In May, as TV comedian John Oliver ran a segment about the issue urging viewers to send the FCC their view, the commission’s website was inaccessible. The FCC said it was “attacked”.

In a joint letter this week, internet pioneers called for the vote’s cancellation, saying the move was pushed through without consultation with appropriate experts and managed by people who simply did not know what they are doing.

Mr Pai received threats towards his family, including signs outside his home. A man in Syracuse was arrested after making death threats against a senator.

In short, the subject has very quickly became extremely politically charged and vicious.

The undeniable result: a complete shut down of constructive dialogue on what could be a defining decision in the internet’s history.

Several things could happen from here. Court challenges could delay implementation of the FCC’s rules, or overturn them altogether. If President Trump – or another Republican candidate – fails to win in 2020, a Democrat-controlled FCC could simply overturn this ruling once again.

Creating a political football out of net neutrality, a pendulum that swings with each new administration, could be causing the most harm to the internet economy.

“Congressional action is the only way to solve the endless back and forth on net neutrality rules that we’ve seen over the past several years,” argues Senator John Thune, a Republican.

“So many of us in Congress already agree on many of the principles of net neutrality.

“If Republicans and Democrats have the political support to work together on such a compromise, we can enact a regulatory framework that will stand the test of time.”

Source: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment