After reading the following article I decided to set what this article was about as a trivia question for the community that use the World Justice News chat facility. The qusetion asked was:

In the USA (at least in most states) under what circumstance is a person under arrest not granted the basic constitutional protections such as Miranda rights, the right to a public defender, and the right to a prompt appearance before a judge?

Read on to discover the answer.

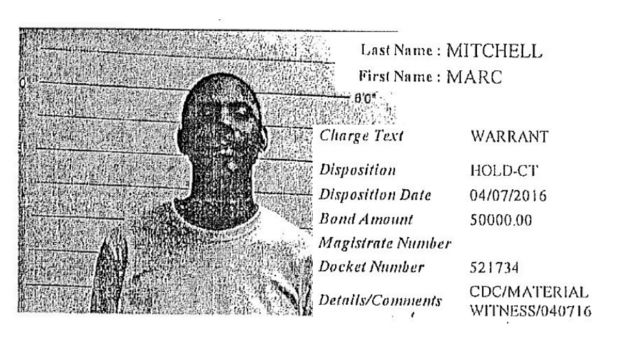

Marc Mitchell was at work when the police came to arrest him, last April, at the New Orleans hotel where he was a houseman. They handcuffed him in front of the customers and staff and took him to jail.

The officers couldn’t tell him why there was a warrant with his name on it, only that the Orleans Parish district attorney wanted him picked up. He didn’t find out until the sheriff’s deputy at the jail read his booking sheet and raised an eyebrow at what she saw.

“She was like, ‘Oh you doing that huh?’,” Mr Mitchell recalled. He didn’t understand what she was saying. “She told me, ‘They got you down here as a snitch’.”

Mr Mitchell was a victim, not a suspect. His booking sheet showed that he’d been arrested on a material witness warrant – a controversial tool used to detain witnesses and victims who prosecutors fear won’t show up to trial.

In July 2014, Mr Mitchell and his cousin were at a public basketball court when they got into a dispute with 25-year-old Gerard Gray, a local gang leader, over who was up next. Gray ordered an associate, Jonterry Bernard, to kill them both. Bernard walked into the park moments later and fired 28 times.

Mr Mitchell, 41, was hit in the chest and leg. He suffered a collapsed lung and was hospitalised for a month. His cousin, Chris Chambers, was hit in the neck and nearly bled to death at the scene. In March 2015, both willingly testified at Bernard’s trial and the gunman was sentenced to 100 years. In April 2016, Gray was due to go on trial and Mr Mitchell had been subpoenaed again to give evidence.

He signed the subpoena which legally obligated him to turn up at court, but told the district attorney’s office he did not want to continue helping them them prepare their case due to safety concerns. “They were not looking out for me at all,” he said.

The DA’s office worried he might not testify. They obtained a material witness warrant, and five days before the trial was due to begin Mr Mitchell found himself at Orleans Parish Jail, under the same roof as the man he was due to testify against, who had already ordered his murder once.

Material witness warrants originate in the early 1800s, when getting hold of a witness who had left a jurisdiction before trial might involve a long day on horseback. They allowed lawmen to lock up key – “material” – witnesses at their convenience.

Sporadic use of the warrants caused little controversy until 9/11, when law enforcement seized on them as a means to detain terror suspects without probable cause. At least 70 men were held as material witnesses in the aftermath of the attacks while the Justice Department looked for evidence, according to a 2005 report by Human Rights Watch. A third of them for were in prison for more than two months, some for more than six months, and one witness detainee spent more than a year in prison.

Someone arrested on a material witness warrant can in theory be detained indefinitely, and in most states detainees are not granted the basic constitutional protections afforded to suspects under arrest, such as Miranda rights, the right to a public defender, and the right to a prompt appearance before a judge.

“Judges grant these warrants largely on the basis of the DA’s word only,” said Ronald Carlson, a law professor at the University of Georgia. “And I think the public at large would be shocked to know that a defendant gets the right to an appointed attorney in a felony case, but there is no such right in many, if not most, jurisdictions for a material witness.”

Orleans Parish, which sits within the most incarcerating city in the most incarcerating state in America, is one of those jurisdictions. The DA’s office there says it does not keep records of when it requests a material witness warrant, but a local non-profit justice watchdog, Court Watch NOLA, undertook a time-consuming trawl through case files and found at least 30 cases last year in which one was issued.

In one case, a female rape victim was jailed for eight days after refusing to co-operate with a prosecution. In another, a domestic assault victim was jailed for six. Both were in the same jail as the perpetrator. Other cases included male victims of assault and attempted murder.

“The level of trauma of being incarcerated in the same facility as your aggressor is a deep concern to us,” said Simone Levine, executive director of Court Watch NOLA. And without the automatic right to a attorney, she said, “often the only person telling a victim why they’re being incarcerated and what their options are is a police officer”.

That was the situation Marc Mitchell found himself in that day at Orleans Parish Jail – a facility facing a lawsuit from the Department of Justice over poor conditions, understaffing and high levels of violence.

“That is not a safe facility for anyone,” said Ms Levine, “let alone witnesses.”

‘I was scared for my life’

As he waited to be assigned a cell, Mr Mitchell called his girlfriend from the jail phone. She frantically quizzed him about whether they would put him in protective custody. She knew he was in the same jail as Gray, who prosecutors later described at trial as “the leader of one of the most murderous gangs in town”.

“I was scared for my life,” Mr Mitchell said. “I was not safe in there because of what was written on my paperwork. And I wasn’t put in protective custody, I was in with the worst of the worst. My cellmate was only allowed to leave the cell to take a shower.”

Mr Mitchell couldn’t afford to pay his $50,000 bond, so he faced the prospect of staying in jail until the trial began five days later, or longer if proceedings were delayed – which they were. Luckily, he had a friend who worked in the courthouse, who visited the judge in the case, Laurie White, the following day.

Judge White told the BBC that the DAs office portrayed Mr Mitchell as a serious flight risk, telling her he had bought a bus ticket out of town. The DA’s written application for a warrant described a meeting with Mr Mitchell, painting him as un-cooperative, but neglected to mention that at the same meeting he signed a legally-binding subpoena to appear at the trial.

A spokesman for the DAs office said Mr Mitchell made repeated verbal threats not to appear, which Mr Mitchell denies. “That was news to me, and I didn’t know nothing about any bus ticket,” he said. “I had every intention of testifying. There was no need to lock me up at all.”

Judge White reversed the warrant and had Mr Mitchell released. “I was very concerned about his safety,” she said. “In the end he was a fantastic witness. It was a horrific crime and he should have been afraid, but he came to court and the perpetrator got a long sentence.”

She said she is “now not so quick to issue any material witness bond requested by the DAs office until I find out more”.

Four days after Mr Mitchell was released, he was sacked. He is still unemployed, save for odd jobs in construction.

“Even a couple of days in jail can destroy someone’s life,” said Colleen Kane Gielskie, a spokeswoman for the American Civil Liberties Union in New Orleans. “It sets off a cascading effect, you can lose a job, lose custody of children, all kinds of things that can have lasting consequences.”

Fake subpoenas and a pattern of coercion

Rights groups in Orleans Parish allege that the use of material witness warrants form part of a pattern of coercion by a DAs office chasing prosecutions at all costs. Court Watch NOLA fears there are many more cases than those unearthed by its report, and that the threat of imprisonment is being used, unchecked, to intimidate victims and witnesses.

“It doesn’t always result in an arrest warrant,” said Mary Claire Landry, executive director of the New Orleans Family Justice Center, “but the tactic of using the threat of jail to intimidate victims and witnesses is being used on a regular basis. We hear about it directly from survivors.”

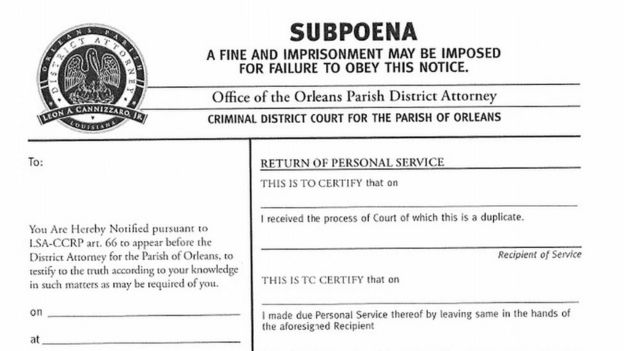

The Orleans Parish DA’s office was forced to apologise last week after it was found to have been issuing so-called “DA’s subpoenas” – a fake subpoena which warns witnesses that they could be fined or sent to jail for ignoring it, despite having no such authority. A spokesman for the DA said the office would immediately stop issuing the notices.

At the centre of the controversy in Orleans Parish is District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro, who angered victim rights groups earlier this month when he described jailing victims as an “inconvenience” that he would continue to regard as necessary to getting convictions.

“No one takes any great pleasure in asking a judge to sign a warrant to have a victim or witness arrested,” Mr Canizzaro told the BBC. “It is the exception, not the rule.”

He pointed out that the DA’s office employs trained victim advocates and argued that it used jail only as a last resort. In the case of the rape victim identified by Court Watch NOLA, he said other means of getting her to testify were exhausted before she was jailed.

“We did what we thought was appropriate to preserve the case and convict someone we thought was a violent offender,” he said.

But Mr Cannizzaro is increasingly under pressure to curtail the practice. New Orleans City Council passed a resolution 6-1 on Thursday calling on him to stop jailing victims, although the resolution has no legal force. He hit back at the council members, calling on them to “focus their attention on a violent crime problem that is spiralling out of control”.

There is very little state-level data on the use of material witness warrants and the national picture is almost entirely opaque. A handful of high-profile cases have thrown a spotlight on the practice in the past, casting doubt over the reliability of evidence produced by detained material witnesses and exposing mistreatment of vulnerable victims.

In 2010, Jabbar Collins was released from prison after serving 16 years for murder when it emerged that a material witness had been detained in a Brooklyn hotel room until he agreed to testify against Collins. Other witnesses had been threatened.

The case revealed an allegedly routine programme of detaining witnesses in hotel rooms, without access to counsel or a phone, and Mr Collins successfully sued the city for $10m (£7.7m), and the charges against him were vacated.

Then-Brooklyn district attorney Charles Hynes and his top assistants were accused of running rogue with material witness warrants. Mr Hynes’ successor dubbed the practice “Guantanamo on the Hudson”.

In 2015, 56-year-old Russell Hernandez was released after two years without charge at Rikers Island prison on a material witness bond. Mr Hernandez served more time than the two men who robbed him and never even testified, because they took a plea deal. He won $1m in compensation.

The same year, in Houston, a young rape victim who suffered from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder broke down on the stand at the rapist’s trial and fled, saying she could not continue. The woman, named only as Jenny, was arrested and jailed for 27 days in the prison’s general population, where she said she was beaten by guards and inmates.

Harris County DA Kim Ogg, who took office after the incident, has instructed her prosecutors never to seek a material witness warrant against a victim in a sexual assault or domestic violence case, and discouraged the use of the warrants generally.

Under a new bill being championed by Ms Ogg – Jenny’s Law – victims and witnesses threatened with jail in Texas would automatically have the right to a public defender and to appear promptly in front of a judge.

“We need to ensure that when we use such a powerful tool as depriving someone of their liberty we give them a chance to respond, in person, with counsel, in open court, and ensure that process is scrutinised,” Ms Ogg said. “These are basic rights that are given to the accused. They should be given to the victim too.”

Mr Cannizzaro said he respected the position of the victim rights advocates in Orleans Parish, but declined to rule out using jail as a tool.

“This is what I say to victims: give me a chance to help you. Don’t just make a complaint and run away and think magically the bad guy is going to be automatically convicted and go to jail. Our system does not work like that,” he said.

But critics of the warrants say the patchwork of different state laws and lack of transparency around them is open to abuse. Professor Carlson has called for national law reform, and created a model statute which would grant material witnesses basic rights and protections and prohibit them being held in the same facility as the perpetrator.

“Bringing witnesses to trial is a balancing act,” he said, “but that balance can end up very costly to the citizen who witnesses or suffers a crime, comes forward, and then gets told they’re going to jail until the trial.”

The balance in Orleans Parish cost Marc Mitchell his job, but he was fortunate to have friends and family who could petition the judge on his behalf. Without the right to a public defender or hearing, there are no guarantees.

Source: With special thanks for a super and informative article: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment