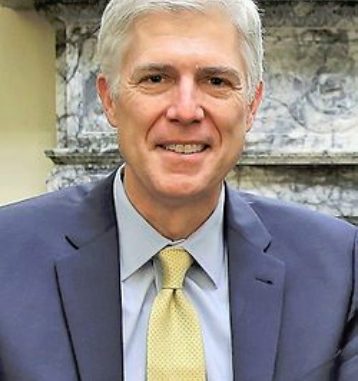

In a hearing that stretched through nearly 12 hours Tuesday, the Supreme Court nomination of Neil Gorsuch took a long step toward Senate confirmation. Barring an utterly unforeseen reversal when the questioning resumes Wednesday, observers expect Judiciary Committee approval along party lines on April 3 and a similar win on the Senate floor.

Twenty senators took turns asking questions for half an hour each. The Republicans tried to get the country to share their affinity for the nominee. The Democrats tried to tie him to President Trump.

The nominee himself tried to project an affable, likable and even folksy persona to go with his stellar legal credentials.

Of course, many who tuned in may have just been trying to stay awake. If you follow Supreme Court jurisprudence obsessively and can use the phrase stare decisis in a sentence, you were mesmerized. Otherwise, you were more likely anesthetized.

The proceedings simply did not live up to the expectations of those who witnessed the battles over High Court nominees in each of the past five presidencies — some of which made for high drama, indeed.

To some degree, this was testament to Gorsuch’s own temperament. He kept an even keel throughout the day, rarely betraying more than a hint of impatience or pique. He smiled a lot, made jokes about family and matched the mood of each of his interrogators.

Ever hear of “mutton busting?” Gorsuch explained it was bronco busting for kids (they hang on to handfuls of wool on the backs of sheep). We heard more than once about how, at the age of 9, he was walking precincts for his politician mother. And then there were those games of HORSE the Supreme Court clerks played with Justice Byron White…

But there were also sober exegeses about sending people to federal prison “for a long, long time” and the sanctity of human life at all stages and the prime importance of limiting the reach of the federal government.

By day’s end there were surely those who had been charmed and won over by the mixture of erudition and aw shucks. But there were also those who heard legal theories and attitudes akin to those of current Justice Samuel Alito and Chief Justice John Roberts.

The memory of Thomas’s confirmation hearings in 1991 was one of several ghosts (or penumbra, to borrow a term from the landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade) emanating around the edges of Tuesday’s session. Thomas was nominated to the top court in 1991 by President George H.W. Bush, replacing Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first African American to reach that pinnacle. Thomas squeaked through on a narrow Senate vote, mostly because he was accused of sexual harassment by a former colleague (Anita Hill).

But even before Hill’s accusations emerged, Thomas was raising eyebrows by avoiding answering questions about controversies. Asked about Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationwide, Thomas insisted he had not formed an opinion about it — even though he was a law school student when the ruling shocked the nation in 1973.

Democrats greeted that bit of Thomas memoir with incredulity, but they knew why Thomas was refusing to engage. In the late 1980s, a more truculent acolyte of conservative judicial theory, Robert Bork, had been named to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan. Through tempestuous days of hearings, Bork espoused his back-to-the-roots theories of the Constitution and said he was looking forward to “an intellectual feast.”

The Democrats grilling Bork in 1987 had just taken back control of the Senate majority and were spoiling for a fight with Reagan. Bork gave them one, and it turned out to be one they could win. Bork was rejected first by the Judiciary Committee and then by the full Senate. To this day, some in Washington cite the Bork episode as the bilious wellspring of extreme partisanship so familiar in the capital for 30 years since.

Supreme Court nominee Judge Robert Bork testifies on the fourth day of his Supreme Court confirmation hearing in Washington, DC, in 1987. Nominated by President Reagan, Bork was ultimately rejected by the Senate.

Following those traumatic interludes, the naming of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993 by President Bill Clinton was something of a relief. Ginsburg was the court’s second woman and she was magisterial in her hearings. She set parameters for a nominee, talking about how even a hint of her predisposition toward a given case or question would undermine the entire judicial system.

Things got more contentious again when President George W. Bush nominated two hardcore conservatives in 2005: eventual Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. Both followed the “Ginsburg standard” to the letter, deflecting questions about key cases and legal issues. The Republican majority in the Senate meant both would glide through so long as Democrats were denied a plausible cause for a filibuster.

No filibuster came about, but Alito came closest to such a challenge. He was not as glossy as Roberts, and Democrats entertained thoughts of drawing a line in the sand. Then came the day Alito’s wife left one of the hearings in tears, overcome by a litany of nasty things being said about her husband. The video and still pictures played and played, and that was that.

President Barack Obama had the distinction of nominating not one but two women to the top court. The first was Sonia Sotomayor, who got some flak for her statements about “a wise Latina” making better decisions in some cases. Her hearings were also fraught with racial overtones because, as an appellate judge, she had ruled in a controversial case regarding firefighters and race — one from which Republicans such as Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions (now the U.S. attorney general) thought she should recuse herself.

But Sotomayor was confident and a touch defiant in her hearings, and Democrats had nearly 60 seats in the Senate at the time. Obama’s next choice was the witty and, at times, acerbic Elana Kagan, who 15 years earlier had penned a Harvard Law Review article calling the post-Bork hearings for the Supreme Court “a vapid and hollow charade” because the nominees gave “evasive answers.”

When Kagan’s own turn in the dock arrived, she was a good deal more circumspect in her own answers, as well.

Supreme Court Justice nominee Elena Kagan answers questions from members of the Senate Judiciary Committee on the second day of her confirmation hearings on Capitol Hill in 2010 in Washington, DC.

All these nominees went before the bright lights and cameras in the Senate hearing room amidst an atmosphere of apprehension and uncertainty. Would there be a landmine in the road, a torpedo in the water? It was as if the defeat of Bork and the near-defeat of Thomas had heightened the natural anxiety attached to a position of such historical significance.

There is, by contrast, almost no tension at all around the Gorsuch nomination. He is all but certain to be confirmed. Much of the intrigue and drama is gone when you know that the Senate’s Republicans can either confirm him with their own majority of 52 votes or, in the event of a filibuster, change the Senate rules to prevail.

But the Democrats, driven by the post-election rage of their own base, will continue to resist Gorsuch as a surrogate for Trump, whom Sen. Richard Blumenthal spoke of as “the elephant in the room.”

They will fashion Trump’s vow to nominate a judge “who will overturn Roe v. Wade” as an albatross around Gorsuch’s neck. They will pound away at his curious opinion in the TransAmerica Trucking case involving a truck driver fired for leaving his disabled rig in subzero weather. The court on which Gorsuch serves sided with the trucker, Gorsuch went with the employer.

Blumenthal and other Democrats also brought up Trump’s disparagement of the Hispanic judge in the Trump University fraud case. Gorsuch repeated his earlier statement that: “Attacks on judges’ integrity are disheartening and demoralizing.” The White House immediately sent a Tweet saying this remark was not meant to pertain to the president. This claim prompted guffaws and disbelief, and for a time distracted from the overall smoothness of the Gorsuch performance.

It is not unusual for the opposition party to put the sitting president on trial in a hearing for one of the president’s nominees. But in this case, it is not likely to work. In personality, resume and demeanor, Gorsuch remains too much the anti-Trump for the two men to be equated in the public imagination. And that is likely to be the bottom line on these hearings and the coming votes in the committee and the full Senate.

By Ron Elving

Source: npr.org

Be the first to comment