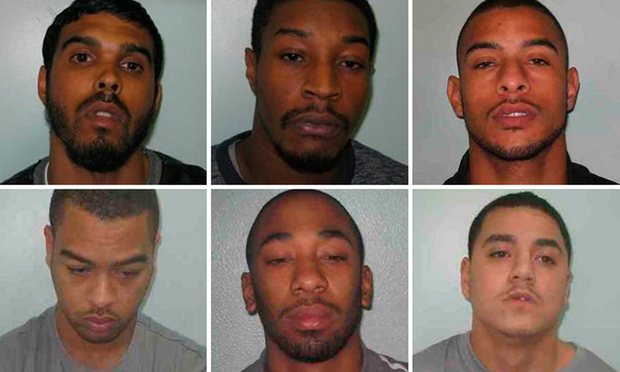

Judges have refused to overturn guilty verdicts against 13 men convicted using the law of “joint enterprise”.

The test cases were brought after the Supreme Court ruled the controversial law had been interpreted wrongly for more than 30 years.

It has allowed people to be convicted of murder even if they did not inflict the fatal blow, but “could” have foreseen violent acts by others.

There were shouts of “no justice, no peace” when the new judgement was made.

The Supreme Court said in February it was wrong to treat “foresight” as a sufficient test to convict a defendant under the law and juries had to decide on the “whole evidence”.

But in his judgement, Lord Neuberger said the decision did not automatically mean all previous joint enterprise convictions were unsafe.

Many of those jailed under joint enterprise rules for secondary roles in crimes have been handed extremely long sentences because judges’ ability to exercise discretion in individual cases was curtailed by the imposition of mandatory life tariffs for murder under the 2003 Criminal Justice Act.

The law of joint enterprise, also known as “common purpose”, where someone acts in conjunction with the killer but does not strike the blow that causes death, dates back to at least the 16th century. It was later developed to deter duelling by making seconds and doctors liable for murder.

In 1984, Sir Robin Cooke, a senior judge, decided an appeal case from Hong Kong in the judicial committee of the privy council declaring that foresight alone of what an accomplice might do was sufficient to prove guilt.

His ruling, lowering the threshold of proof, set a precedent that was followed throughout British common law jurisdictions. Over the past decade the legal principle has frequently been used to thwart gang violence.

In February, however, five supreme court justices ruled that courts had misinterpreted the foresight rule. In a damning assessment, Lord Neuberger, president of the supreme court, said that the line of legal reasoning introduced in 1984 had been in “error”. Foresight of what someone else might do is merely part of the evidence. “It is for the jury to decide on the whole evidence,” Neuberger added, “whether [a secondary party] had the necessary intent.”

That ruling, on the case of Ameen Jogee, did not result in mass releases but concluded that disputed cases would have to go back before the court of appeal to have the specific facts of the each conviction re-examined. Jogee’s conviction was quashed and he will face a retrial.

Be the first to comment