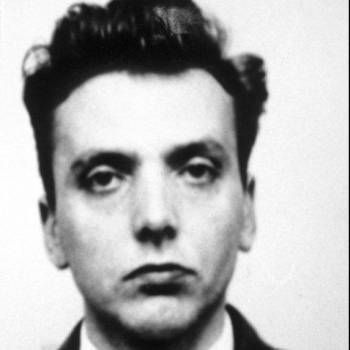

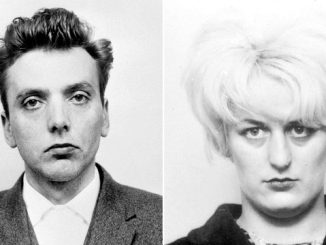

- Moor Murderer Ian Brady has died at the age of 79 after batting lung cancer

- The killer murdered five children alongside Myra Hindley in the North West

- He tortured them and four of his victims were buried on Saddleworth Moor

Moors murderer Ian Brady, who killed five children alongside Myra Hindley, has died, Ashworth Hospital has confirmed.

The child killer was receiving end of life care at the secure mental hospital where he was being detained in Merseyside.

In December it was revealed that he was suffering from inoperable lung cancer.

Brady, and his co-accused Hindley murdered Pauline Reade, 16, John Kilbride, 12, Keith Bennett, 12, Lesley Ann Downey, ten, and Edward Evans, 17.

The pair tortured the children in the 1960s and four of the victims were buried on Saddleworth Moor in the South Pennines.

Brady was jailed for three murders in 1966 and had been at Ashworth since 1985. He and Hindley later confessed to another two murders.

In 2013 he asked to be moved to a Scottish prison so he could be force-fed – as he could in hospital – and where he could be allowed to die if he wished.

His request was rejected after Ashworth medical experts said he had chronic mental illness and needed continued care in hospital.

In February he was refused permission to launch a High Court fight to have the lawyer of his choice representing him at a tribunal where the decision would be reviewed.

Terry Kilbride, whose brother John was murdered by the pair told The Sun: ‘We’ll certainly celebrate his death when it comes. Good riddance.’

However, his death has reduced the likelihood of the family of 12-year-old Keith ever being able to recover his body.

Mr Kilbride continued: ‘I would beg him to do the right thing on his deathbed and tell us where Keith is. Now is the time for him to stop playing tricks and come clean.

Hindley died in prison in 2002 aged 60.

Few murderers have so haunted the public imagination as did Ian Brady, who has died aged 79. There was the horrific nature of his crimes. Between 1963 and 1965, he and his accomplice, Myra Hindley, tortured, sexually abused and killed five youngsters before burying their bodies on the moors outside Manchester. There was the tape recording they made of the last tormented hours of 10-year-old Lesley Ann Downey, as she begged for her mother. It was played to the jury at the time of their trial in 1966. And there was the us-against-the-world bond between them that joined Brady and Hindley, collectively the Moors murderers.

Initially, after they met as colleagues at the factory where they had each worked in Manchester, their relationship served to encourage each other to ever deeper depths of depravity. At their trial, they demanded to be judged as one, but during their long years of imprisonment, love turned to hatred and paranoia, with each blaming the other for taking the lead in their crimes.

Brady’s efforts to scupper any hope Hindley and her high-profile supporters nurtured of parole were always made in letters. Between 1966, when he was given a life sentence at Chester assizes, and 2013, he was neither seen or heard outside of his confinement. But then he insisted that a mental health tribunal hearing, concerning his wish to be moved from a secure psychiatric hospital to a prison, be held in front of the cameras. It was only the second time that such a request had been granted by the authorities.

And so both the families of his victims – some still hoping that Brady might give a clue as to the whereabouts of the missing body of Keith Bennett, aged 12 – and a fascinated public audience were able to watch him at the proceedings via a videolink from Ashworth secure hospital at Maghull on Merseyside. Brady, sheltering behind dark glasses, offered not a word of remorse. He described his crimes, the tribunal heard, as “existential exercises, personal philosophy and interpretation”, and claimed that the murders were “petty compared to [the deeds of] politicians and soldiers”.

While Brady argued that he was sane, and had been faking mental illness while behind bars, his behaviour suggested the opposite. When confronted by evidence he did not want to hear, he walked out. The tribunal finally upheld the view of medical experts who described him as psychotic, paranoid, hallucinatory and as having a “severe narcissistic personality order”. The whole tribunal, and its broadcast, was, they argued, evidence of Brady’s still unquenched desire to draw attention to himself, to control situations, and to have things on his own terms.

He was born Ian Stewart in the rundown Gorbals area of Glasgow, and was abandoned by his natural mother at three months. Peggy Stewart, an unmarried waitress, would only say that the child’s father was a reporter on a Glasgow newspaper. She put a card in a shop window offering her baby son for adoption. He was taken in by the Sloans, a well-meaning couple in their 40s with several older children. Though poor and living in cramped accommodation, they treated the new arrival with kindness. He remained distant from them, seldom joining in family life.

When Brady was nine, the Sloans moved to an overspill estate at Pollok. A friendless boy at school, Brady was, his teachers recalled, neat, polite and delicate. Fellow pupils later told a different tale. During a routine game of cops and robbers, they reported after Brady’s trial, their classmate had tied a boy up and set fire to him. On another occasion he had boasted of burying a cat alive.

As a teenager, he became ever more solitary, with hobbies that appeared odd to others, such as collecting Nazi souvenirs. He also became a hoarder of pornography. Such interests required more money than he had and at 14 he was bound over for petty burglary. Though bookish – at 15 he was reading Dostoevsky – Brady never managed to direct his enthusiasms into academic achievement and left school with no qualifications. At some stage in his late teens, his attitude towards the rest of the world shifted from self-imposed isolation to antagonism.

He was working at a butcher’s shop in Glasgow when he was arrested by the police again. As an alternative to going to prison, it was decided in December 1954 by his adoptive parents and probation officers that he should be sent to Manchester to live with his natural mother. She had by now married Pat Brady, a market porter, and was living in Moss Side.

Brady adopted his stepfather’s name and seemed to settle well, until he was caught stealing again. It was a recurring pattern in the next few years. A period of exemplary behaviour was followed by a return to petty crime. He was sent for a year to borstal, where he studied book-keeping. Returning home on release in November 1957, he landed a job at Millwards chemical factory as a clerk.

In January 1962, he met Hindley, a young typist there. With his cold grey eyes, boney face and aloofness, he quickly had her enthralled. She was later to describe him as her “god”. Bathing in the glow of her adoration gave him the confidence to believe his grisly dreams could become reality. An awkward teenager from a dysfunctional background, Hindley later recalled that at first sight Brady seemed to her to be dripping with glamour, with his veneer of learning, his knowledge of wartime history and his penchant for writers that she had never heard of, such as the Marquis de Sade. He was also sexually uninhibited.

The two began an intense relationship based on a mutual dislike of the rest of society and their preference for Brady’s bizarre and perverse fantasy world. In July 1963 those fantasies turned to murder when Hindley and Brady lured 16-year-old Pauline Reade on to the moors above Manchester, where Brady killed her and they buried her body. Brady had been obsessed with bleak, open spaces since his first ever trip outside Glasgow, aged nine, to Loch Lomond.

Though Hindley made efforts to break away – even toying with joining the police – she and Brady went on to kill 12-year-old John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey and Edward Evans, aged 17. Shopped to the police by one of Hindley’s relatives, Brady remained silent and defiant thoughout their trial as to the full extent of the couple’s crimes. (He was later to boast there were more victims, but police found no evidence for this.)

For almost two decades after they were jailed for life (Hindley was sent to Holloway, Brady at first to Durham), Brady was held for the most part in solitary confinement, his only regular contact with the outside world the long, rambling and often confused letters he sent to the prison reform campaigner Lord Longford. When Longford published extracts from these in one of his books, the distinguished academic AL Rowse wrote to him to say that Brady clearly had a brilliant mind.

Longford never made any secret of his view that Brady was, as he liked to put it succinctly, “brilliant but bonkers”. In 1985, partly through the efforts of Longford, Brady was diagnosed as a psychopath and moved to Ashworth. He never forgave the peer and labelled him a “Home Office stooge”, refusing to see him again (though he relented just once, in 1998).

In 1999, Brady began an indefinite hunger strike. At first he said he was protesting at his treatment at Ashworth, which had been at the centre of controversy and was threatened with closure following a highly critical commission of inquiry. But it soon became clear that Brady’s motives were more self-serving. His narcissism caused him to crave the spotlight. He claimed that he wanted to die, but, as the mental health tribunal later heard, he would often administer his feeds himself, and tuck into other provisions.

It decided quickly and unanimously to uphold his detention at Ashworth. After the furore that surrounded proceedings, Brady disappeared once more from public view.

• Ian Brady (Ian Stewart), born 2 January 1938; died 15 May 2017

The Independant

Be the first to comment