Like many other teenagers her age, Bianca Devins lived her life online.

The 17-year-old had recently graduated from high school and was looking forward to starting a psychology course at a community college later this year.

As last Saturday approached, she wrote on a gaming platform about how excited she was to be travelling the 250 miles from upstate New York to a concert in Queens. But before she could return home on Sunday morning, Bianca was dead.

The exact relationship she’d had with the man accused of killing her remains unclear. But in the hours after his arrest, it emerged he had shared graphic photographs of the murder online.

In the days since, her story has spread across the world – as have the violent images of her death.

Her murder, which played out so publicly, is the latest case to place scrutiny on how social media companies police extreme content. Here, we detail how Bianca’s murder was shared and exploited online in the hours and days after her death.

“Here comes Hell. It’s redemption, right?”

Brandon Andrew Clark posed that question, taken from a rock song, to his Instagram followers in a temporary 24-hour story posted before dawn last Sunday.

The next image he shared was far more disturbing. A blurry photograph captioned “I’m sorry Bianca” appeared to show a woman’s bloodied torso.

Before then his Instagram account, which we have chosen not to name, was mostly used to catalogue selfies and posts about music and art. Police believe the 21-year-old met Bianca through the platform two months earlier and their relationship had progressed in person since.

On Saturday, he drove Bianca to New York City from Utica, where she lived, to see Canadian singer Nicole Dollanganger perform. Police said they believed the pair had got into an argument on the way back, possibly about her kissing someone else, and he had fatally attacked her with a knife.

Police said the suspect shared an even more graphic photograph of Bianca’s body on Discord – a popular messaging platform for gamers. This image showed the extent of injuries to Bianca’s throat and made clear her wounds had been fatal.

Screenshots from the now-deleted private chat on Discord, apparently used by friends of Bianca, show he shared the image at about 06:00.

As concerned friends scrambled to work out if the photo was real, the suspect continued to post offensive content in the group. Members then took screengrabs of the messages and of his Snapchat account and raised the alarm.

By 07:20, Utica Police had received “numerous” calls, including some from other US states, about the disturbing posts. Police said the suspect had also called 911 himself and made “incriminating statements” about his actions.

When an officer tracked him down to a wooded area at the end of a residential road, he stabbed himself in the neck. He then lay down on top of a tarpaulin, which police said he had placed over Bianca’s body, all the while taking and posting more photographs online.

After a brief struggle, the suspect was arrested and taken to hospital. A day later, after emergency surgery, he was charged with Bianca’s murder.

Image: @beegtfo

Image: @beegtfo

How news of the murder spread

Instagram has not confirmed when it received the first reports about the violent image on his public story. But as Sunday rolled on, word was beginning to spread beyond Bianca’s social group, much of it clouded by misinformation.

By Sunday evening, users on Twitter had started to talk about and re-share the Instagram posts. Other users implored people to avoid watching his story and report the account.

From the outset, users said their reporting attempts were being rejected for not violating Instagram’s terms. When approached by the BBC, Instagram did not say how long the original posts on the suspect’s story had been allowed to stay up, but screenshots suggest they had been publicly available for more than 20 hours.

Dr James Densley, a professor of criminal justice in Minnesota, said this kind of public violence carried the risk of secondary trauma for viewers, and also re-victimised Bianca herself.

“We have this term for people to rest in peace,” he told the BBC. “Well, really, she can’t, because she’s living in this sort of perpetual infamy online every time her image is shared.”

Some of the first people to discuss the murder were users on website 4chan – a barely moderated internet messageboard where users can post anonymously. Both it, and the even more extreme website 8chan, have become notorious in recent years for the increasingly radical rhetoric posted by some users and their links to a number of deadly attacks.

Before 51 people were shot dead in two Christchurch mosques in March, a manifesto in the suspected gunman’s name was posted to 8chan. He also live-streamed the shooting on Facebook, telling viewers at the start of the attack to “Subscribe to PewDiePie”. This ironic meme, about a popular YouTuber, also appears to have been used by the Utica suspect after he posted images of Bianca’s murder to Discord.

This and other comments attributed to the Utica suspect during the attack echoed the language being used in these extreme online communities, Robert Evans, an investigative journalist who specialises in radicalisation online, told the BBC.

Both the suspect and Bianca are said to have used 4chan themselves in the past. Users on the forum on Sunday celebrated “another 4chan murder” and discussed her death in offensive and misogynistic terms, victim-blaming and even photoshopping the graphic images of her into sadistic memes.

Evans said violent images and language like this were “extremely common” on these platforms. He compared the way that some young men were being radicalised on these websites to how terror groups recruit.

“All you have to do is shotgun out propaganda in the hopes that a couple of times a year, one individual will have enough commitment and hate in their heart to do something,” he told the BBC.

He believes law-enforcement need to take radicalisation on these websites more seriously. “I don’t think IS would get away with proliferating in a place like 8chan,” he said.

“But at the same time – the internet is what is. And I don’t know how you could police every dark little corner of it. This is a very 21st Century problem – and it’s not one with a roadmap to solve it.”

Dr Densley said these websites have become a place where otherwise “lost souls” are able to congregate.

“These are views that in polite society would be massively offensive,” he told the BBC. “I think because it’s an echo chamber, these individuals talk up and amp up one another.”

By Monday, when the police confirmed the images of Bianca were real, the case had already spilled from the fringes of the internet into mainstream social media. For hours #RIPBianca even trended on Twitter in the US.

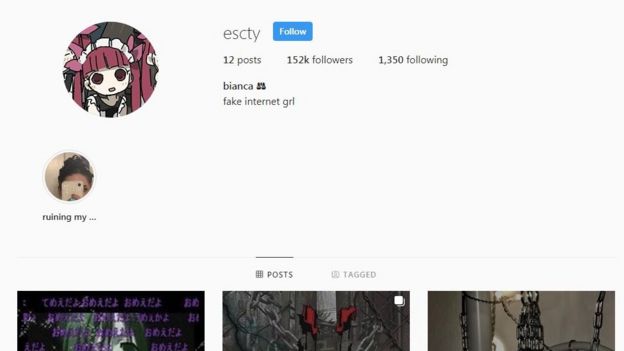

As the story proliferated, some people inevitably tried to search for the accounts and images being mentioned on their newsfeeds. With this attention, the number of Bianca’s Instagram followers started to snowball.

The teenager had been a heavy internet user, but some news outlets drastically overstated the scale of her following. Sensationalist headlines described the murder of an “Instagram influencer” or used the often derogatory and misogynist term “e-girl” to describe her.

In reality Bianca had only about 2,000 followers on her main Instagram account before the news of her killing went viral, according to tracking website SocialBlade. But in the week since, that number has increased to more than 160,000.

The suspect’s account also attracted attraction. Despite his profile being edited to reflect his suicidal intentions at some point during the attack, Instagram did not deactivate it until the police confirmed his identity on Monday, more than a day after the murder. By that time, his following had grown by thousands and his profile was inundated with comments.

Some people capitalised on Bianca’s murder, which had already played out so publicly, as an opportunity to gain followers. Comments like: “FOLLOW ME!!!& DM !! me for full video and picture” were spammed on the suspect’s posts. Dozens of users promised the images of her body were hidden within their private pages. Others tried to trick people into seeing cruel memes or even products they were trying to sell.

Some even went as far as to change their username, or create brand-new accounts, to mimic the suspect’s handle and lure people searching for the photographs.

One person behind one of these accounts, when challenged in a message about their motivations, said they had changed their name out of curiosity but did “feel a little guilty” for the victim and her family. They initially vowed to stop, but about an hour after abandoning the handle, reverted to it.

Another person emulating the suspect’s username told the BBC they did so “for social media clout”, adding: “People will do anything that gains them followers and some popularity.”

On Tuesday, that user claimed to have amassed more than 1,000 follower requests and about 100 messages. They even considered trying to solicit online payments for the images, they said.

Instagram told the BBC it is reviewing hashtags and accounts where people were claiming to share the graphic content. At the time of publication, most of these appeared to have been removed.

The problem social media companies face

Dr Densley said cases like Bianca’s exposed the “weird incentive structures” that exist across the social media we use every day.

“The entire enterprise is built on the number of likes and retweets and friends and followers that you can accumulate,” he said, explaining that people who perpetrate violence online see the value in the online infamy it can bring.

He said those who viewed the violent images then faced a choice: “Do I report it? Do I ignore it and pretend I didn’t see it? Or do I capture it in my own way, and then share it myself?”

The proliferation of images from Bianca’s murder has renewed scrutiny of the way social media is policed day-to-day, just four months after platforms publicly struggled to contain the spread of graphic video from the Christchurch attacks.

Sites like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook do have human moderators – but also rely on artificial intelligence technology and user reports to support their systems. The scale of their membership, which in Instagram’s case is one billion users a month, makes for an overwhelming challenge.

“They use a technique called hashing – which very basically creates a digital fingerprint of an image or video,” BBC technology reporter Zoe Kleinman explains. “This means anything bearing that fingerprint can be automatically flagged and removed, or even blocked at the point of upload.”

“But, it only works if the original material is copied in its entirety. If an image or video is edited or clipped, the “fingerprint” is no longer complete and it can be more difficult to identify.”

Bianca’s case, after that of Christchurch, will do little to alleviate mounting pressure on social platforms from international governments. The UK and Australia have announced new measures where social media companies may face fines, or even criminal charges, if they fail to moderate adequately.

So far this year, Facebook executives have already introduced new restrictions on their live-streaming tool. Instagram also launched new anti-bullying initiatives and a crackdown against self-harm content after the suicide of a British teenager.

Social media companies have reiterated their commitment to their community guidelines since Bianca’s death. Despite this, some graphic content is still slipping through the net. At the time of publication, the BBC found even the most graphic photographs of Bianca’s body – posted up to a week ago – still on Twitter.

How the internet fought back

The day after her murder, Bianca’s stepmother condemned those sharing the graphic images as “disgusting”.

“I will FOREVER have those images in my mind when I think of her. When I close my eyes, those images haunt me,” she posted on Facebook, urging people to consider the feelings of the family and report offensive content.

Many have done so. And many have gone even further, demonstrating how online communities can act as a force for good.

An online spamming war has been launched against those trying to exploit Bianca’s death. Accounts have sprung up to flood tags being used to share graphic photographs and cruel memes of the teenager.

Instead, tens of thousands of pastel-coloured cloudscapes, flowers, hearts and photographs of cute animals – in the style of Bianca’s own selfies – now fill her tagged posts.

Most accounts appear to be run by girls of a similar age to Bianca, who appear to be spending hours on the effort. Often the accounts come with offers of emotional support to others and guidance on how to report upsetting content.

One teenage girl, called Taylor, has shared almost 1,000 “filler” images on the account she set up. “Seeing the images plastered online broke my heart,” she said in a private message from her account. “I wanted to do whatever I could to protect her and her family.”

A 19-year-old named Brianna is among those who created artwork of Bianca as part of the fight to flush out the graphic posts. “I’m glad that her family know that amongst the horror, people still care,” she told the BBC.

Naomi, 21, who is running another “cute clean-up” page, agreed: “I just couldn’t let these monsters win.”

Bianca’s mother, Kimberly Devins, is among those from her family who have embraced #PinkForBianca on their own social media accounts.

In a statement released on Wednesday, she said: “My heart is completely shattered, having lost my best friend. We will always remember her beautiful smile that lit up our lives. Her spirit will strengthen us and live on forever.”

As they prepared for Bianca’s funeral, her family also launched a scholarship fund in her name, in the hope that others can fulfil her dream of helping young people with mental illness.

Kimberly Devins has thanked those who shared support for the family, and implored people to continue spreading the message of “love, not violence” in her daughter’s name.

“You have provided us much comfort in this unimaginably difficult time.”

Source: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment