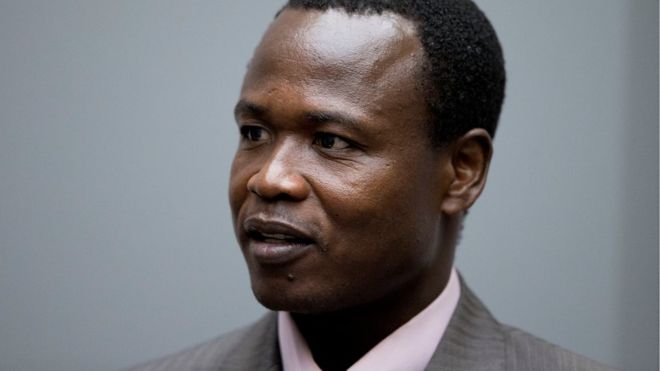

The first former child soldier to appear at the International Criminal Court (ICC) has pleaded not guilty and told judges he was a victim too.

Lords Resistance Army (LRA) commander Dominic Ongwen said the LRA was responsible and he had also suffered from the atrocities.

Ongwen, now in his early 40s, was a boy when he was abducted by the notoriously ruthless rebel cult.

He faces 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Uganda.

Mr Ongwen is accused of leading attacks on four camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) in northern Uganda, murdering and torturing civilians, and forcing women into marriage and children to take part in the fighting.

But he told the court the charges should be brought against the LRA and its leader Joseph Kony, not him.

“It is the LRA who abducted people in northern Uganda, killed people in northern Uganda and committed atrocities in northern Uganda. I’m one of the people against whom the LRA committed atrocities. It is not me who is the LRA,” he said.

When asked if he wanted to plead guilty, he said the trial against him “amounts to my going back into the bush for a second time” and asked the judges if they disputed that his life had been ruined.

Who is Dominic Ongwen?

- Said to have been abducted by LRA at the age of 10 as he walked to school in northern Uganda

- Rose to become a top commander

- Accused of crimes against humanity, including enslavement

- ICC issued arrest warrant in 2005

- Rumoured to have been killed in the same year

- US offered $5m (£3.3m) reward for information leading to his arrest in 2013

However ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said Mr Ongwen was a “murderer and a rapist” who rose to become one of the most senior commanders in the LRA as a result of his “unwavering loyalty and ferocity”.

He was in charge of one of the LRA’s four brigades and most of his soldiers were children, she said.

Mr Ongwen played a “prominent role” in the attacks on IDP camps, she said. Residents were murdered, their homes burned and survivors forced to carry off looted provisions. Those too weak to do this were killed and nursing mothers whose babies slowed them down saw them thrown into the bush and left to die.

In one incident, Ms Bensouda said, Mr Ongwen ordered his child soldiers to kill an old man by biting him and then stoning him to death.

Mr Ongwen also played a “central role” in the LRA’s ongoing abduction of children as young as six.

Boys were made to carry out torture and murder to convince them they could never be accepted back into civilian society, she said.

Girls meanwhile were “held for years in sexual and domestic slavery and subjected to repeated rape”, she said. The defendant himself “benefited most from their misery” and had sex with them “from a very young age”.

Ms Bensouda said Mr Ongwen’s own experience was not a justification for victimising others.

“It cannot begin to amount to a defence or a reason not to charge him for the choice that he made,” she said.

Mr Ongwen was captured in the Central African Republic in January 2015, after being sought by US and African forces since 2011.

He is said to be the deputy to LRA commander Joseph Kony, who is still on the run.

Uganda agreed that Mr Ongwen should be tried by the ICC despite being a fierce critic of the court.

The LRA rebellion began more than two decades ago in northern Uganda and its estimated 200-500 fighters – many of them child soldiers – have since terrorised large swathes of central Africa. More than 100,000 people are thought to have been killed.

How Ugandans are following the trial – Patience Atuhaire, BBC News, Kampala

Many Ugandans are waiting to see if, at least in this situation, justice will be done.

The ICC outreach office and the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) have set up several live-streaming points – in Kampala and in the north for the next two days – to bring the court proceedings to the people directly affected.

Several of these screens are in Lukodi, Pajule and Odek villages, which formerly hosted camps for the internally displaced and are the scenes of many of the crimes Mr Ongwen is accused of.

There is also a live-viewing point in the defendant’s own home village of Coorom in Amuru district.

In northern Uganda, the proceedings are being translated into local language so ordinary people get a sense of what is happening.

Though many are interested in seeing what happens in the Hague, some in northern Uganda think justice is only one part of the process. Many, especially those who suffered years of displacement, are focusing on rebuilding their lives.

Some among those directly affected had wanted Dominic Ongwen to be tried at home.

Be the first to comment