A retired gynaecologist aged 85 has become the first person to go on trial in Spain over a scandal said to have involved thousands of babies being taken from their parents over decades.

Eduardo Vela is accused of abducting Inés Madrigal from her mother in 1969 and giving her to another woman, in the final years of the Franco dictatorship.

He denied signing her birth certificate and did not remember the case.

Dozens of people stood outside the Madrid court appealing for justice.

Inés Madrigal, 49, arrived at the court surrounded by supporters in yellow T-shirts bearing the word “justice”.

“This is not just my case, it has gone beyond that. The whole world knows that in this country children were stolen,” she said.

However, she made clear she did not expect the trial to reveal who her real mother was.

If convicted Dr Vela could face 11 years in jail for illegal adoption and falsifying documents. He denies wrongdoing.

What is the ‘stolen babies’ case?

Campaigners have long highlighted a secret practice of baby abductions during the dictatorship of Gen Francisco Franco which ran from 1939 to 1975.

From the late thirties children would be taken from families deemed “undesirable”, often because they were identified by the ruling fascists as Republicans. They would then be handed to couples often with links to the regime.

In 2008 investigating judge Baltasar Garzón estimated that some 30,000 children had been stolen in the period after the 1936-39 Spanish civil war.

By the 1950s it is thought that organised criminal gangs had become involved in selling infants for adoption for profit.

In 2011 two men, who revealed they had been bought by their fathers, estimated many more adoptions in Spain between 1965 and 1990 involved children taken from their biological parents without consent.

Inés Madrigal says she was abducted in 1969.

The true number of abducted children may never be known.

No answers for victims

By James Badcock, Madrid

More than 100 people who gathered outside the courtroom had come in search of answers – information that could help them locate children or parents they believe were concealed from them by a large-scale baby-snatching network.

What they got in court was an old man, hunched in his seat, his eyes closing as if with extreme tiredness. Dr Vela said he remembered virtually nothing about his 20 years at the helm of the San Ramón clinic that has given rise to dozens of stolen baby claims.

“I didn’t give any baby to anyone,” the gynaecologist mumbled. He said he had no idea what happened to the clinic’s paperwork, which has vanished.

So much time has elapsed that the chances of a stolen baby finding their biological mother and vice versa is sadly remote.

Only this week, with the spotlight back on the issue, have Spain’s main political parties promised to work together to improve victims’ access to archives, a shared DNA database and a more proactive judicial response.

Why is the Madrigal case so significant?

Hers is the only case to have gone to trial, despite thousands of other complaints being filed with the courts.

Last year, another woman was convicted of slandering a nun whom she accused of taking her from her biological mother in 1962 and handing her to an adoptive father who was a senior Franco figure.

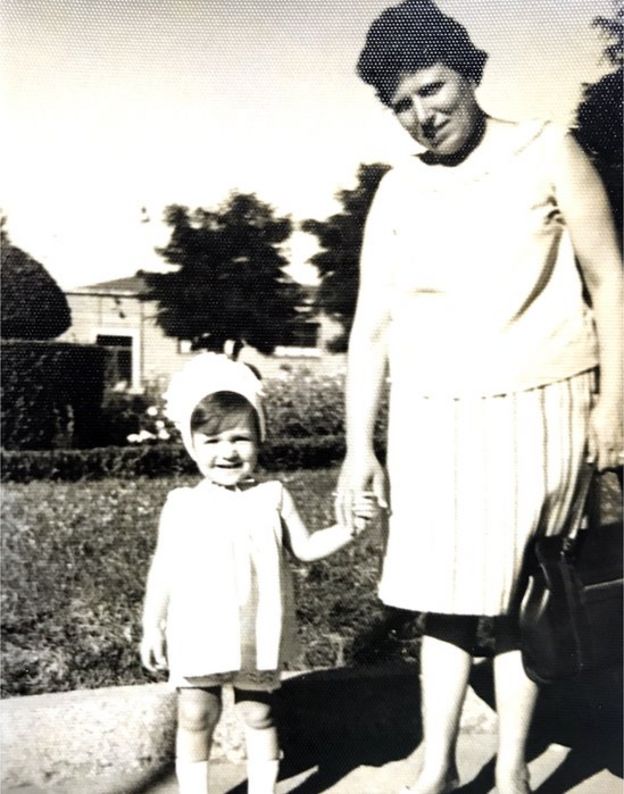

Inés Madrigal was told by her adoptive mother that she had been adopted and, after finding out in 2010 about the emerging “stolen babies” scandal, looked into her own past.

Her adoptive mother, Inés Pérez, told a judge before she died in 2016 that Dr Vela had given her Ms Madrigal as a gift because she could not have children of her own.

Dr Vela has in the past admitted signing the birth certificate that stated Ms Pérez and her husband were the biological parents.

However, when presented with the signature on the document in court on Tuesday he responded with the words: “That is not mine.”

Source: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment