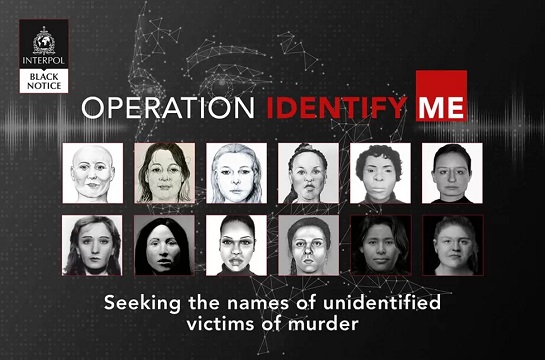

Police in three European countries are asking for help to identify 22 murdered women whose names remain a mystery.

The bodies were found in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany between 1976 and 2019.

An unsolved murder of a woman in Amsterdam, found in a wheelie bin in a river, sparked the move by Interpol.

It’s the first time the international police group has gone public with a list seeking information about unidentified bodies.

The so called black notices, released as part of the campaign known as Operation Identify Me, are normally only circulated internally among Interpol’s network of police forces throughout the world.

The woman found in the bin in Amsterdam in 1999 had been shot in the head and chest.

Forensic detective Carina Van Leeuwen has been trying to solve the mystery since joining the city’s first cold case team in 2005.

Dutch police say a case typically becomes “cold” when it remains open and unsolved after about three years.

Having exhausted all efforts, she and a colleague contacted police in neighbouring Germany and Belgium and learned of many more possible murder cases with unidentified women victims.

The three countries compiled a list of 22 that they were struggling to solve and asked Interpol to publish the details. Belgian police put forward seven cases, Germany six and the Netherlands nine.

Most of the victims were aged between 15 and 30. Without knowing their names or who killed them, police say it is difficult to establish the exact circumstances of their deaths.

The full list – available on Interpol’s website – includes details about the women, photographs of possible identifying items such as clothing, jewellery and tattoos, and, in some cases, new facial reconstructions and information about the cases.

Ms van Leeuwen says finding answers in such cases is vital. “If you don’t have a name, you don’t have a story. You’re just a number. And nobody’s a number,” she explains.

In the Netherlands, almost all of the unidentified bodies of women appear to be murder cases, while – say police – unidentified men died in a range of circumstances.

In that part of Europe, people can go between countries very easily because there are open borders.

Increased global migration, and human trafficking, has led to more people being reported missing outside of their national borders, says Dr Susan Hitchin, coordinator of Interpol’s DNA unit.

It can make identifying bodies more challenging, and women are “disproportionately affected by gender-based violence, including domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking”, she says.

“This operation aims to give back to these women their names.”

Victim number one

The body of the woman found in the bin now lies in a cemetery in central Amsterdam.

Her grave is tucked away close to a train line and behind rows of graves with personalised inscriptions and freshly cut flowers laid out.

She is in an area for those whose names are not known. There, small plaques stick out of the soil with the words “unidentified deceased”.

The woman was found when a local man, Jan Meijer, went out on his boat to retrieve a wheelie bin that his neighbour had spotted floating in the river that runs next to his home on the outskirts of the Dutch capital.

But when he lashed the bin to the boat he noticed it was heavier than he had expected and, as more of it surfaced above the water, he could smell “something awful”.

As a firefighter, Jan had been around dead bodies before. But this stench was visceral. It took him back to an incident in his childhood, when he had found the rotting carcass of a slaughtered sheep.

Upon closer inspection, he noticed the bin had been nailed shut. He towed it to his decking and called the police.

When the bin was prised open, officers found bags of washing powder stacked on top of concrete.

They turned the bin upside down and a body fell to the floor. One of the hands was partly encased in concrete.

An officer who was there tells me the body was grey and looked like a “sand sculpture”. It was impossible to tell from looking if the person was a man or a woman, he says.

The investigation at the time established that the woman was probably in her mid-20s and “partly western European and partly Asian”.

More recent forensic investigations, using isotope analysis, have narrowed down her place of birth to either the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg or Belgium.

“It all has to do with the food that you eat and the water that you drink, but also the air that you breathe,” Ms van Leeuwen says of the technique.

In the weeks following her discovery, police released details of her clothing and shoe sizes and what she was wearing, but they were still unable to identify her. Her dark lace-up shoes with crepe soles were not on her feet but had been put in the bin with her body.

Details of what was found with the body have been released by Interpol as part of Operation Identify Me.

She was wearing a gold-coloured watch on her right wrist and a snakeskin print bag was also found in the bin.

Men’s clothes were also found in the bin – police believe they belonged to the perpetrator. They include a jacket with a red circular symbol sewn into it. Efforts to identify the symbol led to dead ends.

No suspect was ever questioned or arrested in connection with the case, and an initial flurry of media interest soon evaporated.

But for those there on the day the body was found, it was not so easy to forget the woman with no known name. They still wonder who she was – and who might be missing her.

‘They all had somebody who missed them’

When detective Carina van Leeuwen first visited the victim’s grave in 2007 to exhume the remains she felt shocked and saddened at the idea of people falling into obscurity in death.

The owner of the cemetery asked the detective what she planned to do about “all of the others”.

It was then that she realised the scale of the problem with unidentified bodies

Identifying the dead became her specialism and she has gone on to identify 41 people who died from various causes.

All of the bodies she has identified had one thing in common. “No matter how long it took to identify them, they all had somebody who missed them,” she says.

“Even if it’s 25 years later, people are very happy to have something that they can bury and pay their respects to.”

Operation Identify Me

Only four of the bodies Carina has helped to identify in the Netherlands were people from that country, which is why she believes working with police forces across borders, and wider public awareness, is so important.

One of the Operation Identify Me cases is a woman found in Belgium with a distinctive tattoo of a black flower with green leaves and “R’NICK” written underneath.

She was found lying against a grate in a river in Antwerp in 1992. Police said she had been killed violently, but they never discovered her name.

In another case from 2002, a woman’s body was found in a sailing club in the German city Bremen, wrapped in a carpet and bound with string.

Interpol says it hopes that issuing the public list of these black notices will help to prompt memories and encourage people to come forward with any information they may have.

“Perhaps they’ll recognise an earring or specific item of clothing that was found on the unidentified woman,” says Interpol’s Dr Susan Hitchin.

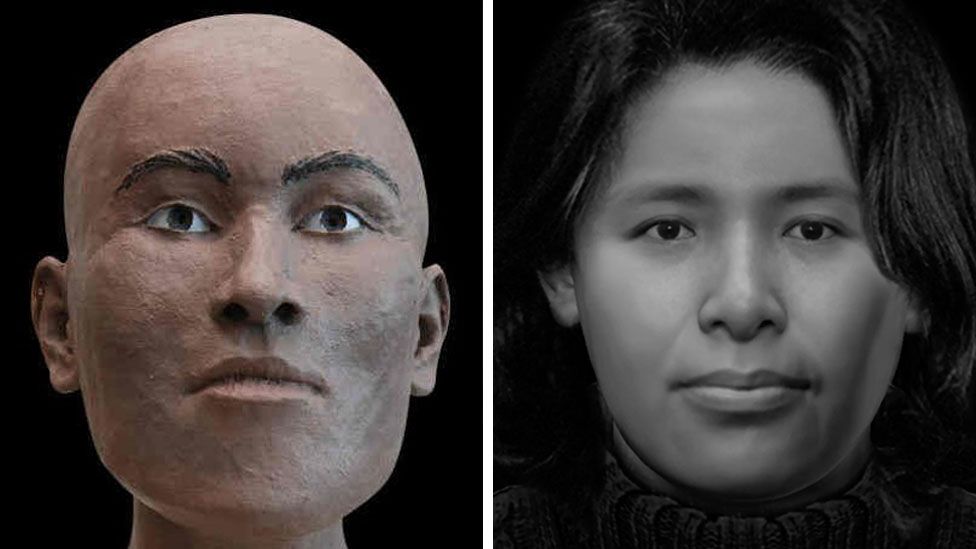

In some of the 22 cases, police forces are using technology that wasn’t available at the time the bodies were found to boost their chances of identification.

A new facial reconstruction of the woman in the bin in Amsterdam has been produced by Dr Christopher Rynn, a forensic artist in Scotland.

He remembers seeing the original post mortem photographs of the woman when he was a student, and they’ve never left him.

He is hopeful that the new image, produced using advanced computer software to reconstruct the face around the skull, will help uncover new leads.

Carina says that – while she would like to solve the case and find the perpetrator – for her “it’s all about [the woman’s] identity, just to give her back to the family”.

She says she will “never give up” on the woman in the bin, or the others she is investigating.

“You’re a person, you have a name, you have a history, and the history has to be told until the end, even if the end is tragic and horrible.”

Source: bbc.co.uk

Be the first to comment