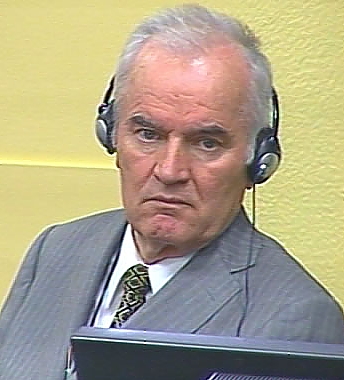

Ratko Mladic, whose war crimes trial reaches a climax next week, is a former Serb army commander whose brutish leadership during Bosnia’s 1990s conflict was blamed for the worst atrocities in Europe since World War II.

The 74-year-old came to symbolise a barbaric plan to rid multi-ethnic Bosnia of Croats and Muslims, fuelled by the desire for a “Greater Serbia” that would establish an ethnically pure state.

The epitome of Serb defiance after the breakup of Yugoslavia, Mladic once said chillingly: “Borders are always drawn in blood and states marked out with graves.”

Closing arguments in his protracted UN war crimes trial at The Hague begin on Monday, with families of the victims in Bosnia’s 1992-95 conflict waiting anxiously for its completion.

The wartime Bosnian Serb military chief, who has been dogged by health problems in detention, will long be associated with the 1995 Srebrenica massacre of 8,000 Muslim men and boys in a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

But his role in the conflict made him a hero to many Serbs and a one-time favourite of the late Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic — himself a fanatical nationalist who was also indicted for war crimes.

Mladic is also accused of being the architect of the bloody 44-month siege of the Bosnian capital Sarajevo, which claimed an estimated 10,000 lives, according to the UN war crimes indictment against him.

The defiance of the man dubbed the “Butcher of Bosnia” by international media seems undimmed by age and years on the run, and he insists he was only “defending my country”.

Born on March 12, 1942 at Bozinovici in eastern Bosnia, Mladic was named Ratko, a diminutive of a Serb name meaning war and peace, usually given to a male baby during wars, his biographer Ljiljana Bulatovic wrote.

His life was quickly struck by bloodshed and tragedy when aged two, his father was killed by the Ustasha, Croatia’s World War II fascist regime.

In June 1991, as Yugoslavia crumbled and war broke out in Croatia, Mladic, then a colonel in the Yugoslav National Army, was given the task of organising the Serb-dominated army in Croatia.

The following May, Mladic, by now a general, was made commander of the Bosnian Serb forces and fought to link Serb-held lands in eastern and western Bosnia.

Former Yugoslav army spokesman Ljubodrag Stojadinovic described Mladic as “narcissistic, conceited, vain and arrogant,” while a former colonel, Gaja Petkovic, said he was a “cynic and a sadist”.

Mladic’s daughter Ana, unable to cope with the burden of accusations of his wartime crimes, committed suicide in Belgrade in 1994 aged 23, reportedly with her father’s favourite pistol.

Those close to the general were reported as saying her suicide pushed him over the edge.

A year later, Mladic was accused of setting in motion Europe’s worst atrocity since the Nazi era, with his troops rounding up and killing Muslim men and boys in the UN-protected enclave of Srebrenica.

In under-siege Sarajevo, the ferocious Mladic refused to bow to Western demands to withdraw his heavy weapons and it took the combined might of NATO warplanes and cruise missiles to blow apart his military advantage in September 1995.

Never just a simple soldier, Mladic once enjoyed considerable political influence within the Bosnian Serb leadership and was never shy of using it.

He was indicted by The Hague-based International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in July 1995, a few months before the war ended, on charges of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

After the conflict, Mladic became too much of a liability and was sacked by the Bosnian Serb government in 1997.

For a long time he holed up in his former main command bunker, calmly defying NATO attempts to arrest him before moving to the Serbian capital Belgrade in 2000.

At first he lived openly, but soon went underground as his popularity waned amongst Serbian politicians, increasingly concerned that failure to transfer him to the ICTY would further delay the country’s accession to the European Union.

Mladic was finally arrested in May 2011 at a relative’s house in northern Serbia and transferred to the Hague to stand trial.

By KATARINA SUBASIC (AFP): DigitalJournal.com

Be the first to comment